The goals in planning the rhinoplasty surgery are to approximate the ideal nose while at the same time considering the patient’s facial structures, gender, and ethnicity. The specific goals are of course, directed by the patient, as long as the goals are reasonable and attainable. There are specific maneuvers that are performed during rhinoplasty that will predictably achieve a specific goal (aesthetic result). The key to patient satisfaction is reasonable expectations.

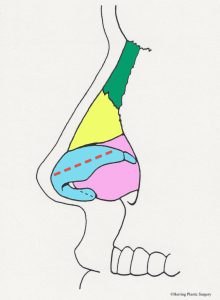

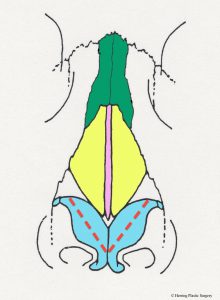

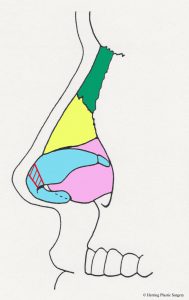

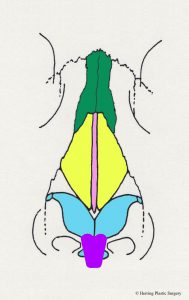

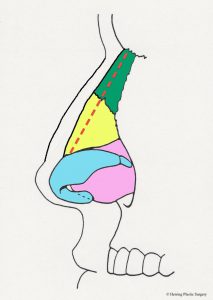

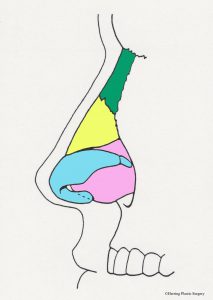

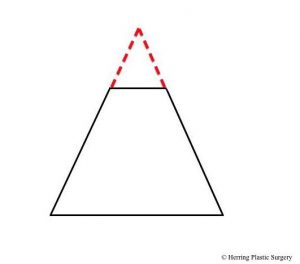

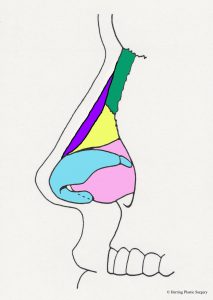

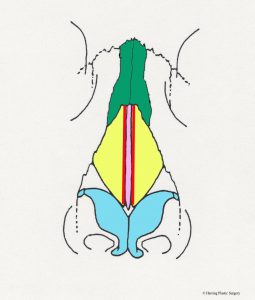

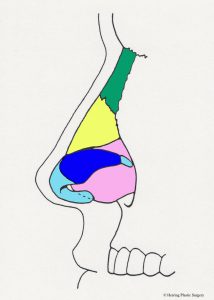

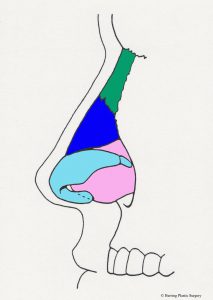

The alar (lower lateral) cartilage is one of the structures that supports and gives the nasal tip shape. If the goal of a rhinoplasty procedure is to change the shape of the nasal tip, then the natural alar cartilage is (usually) altered. The surgical alterations of the alar (lower lateral) cartilages should take into consideration the patient’s facial shape, gender, and ethnicity in order to achieve the best “match.” There are many surgical maneuvers that are routinely performed during rhinoplasty and one of the basic maneuvers is alteration (removal) of the top half of the alar (lower lateral) cartilage. The alar (lower lateral) cartilage is light blue in the diagram below. The image below is a diagrammatic view of the nasal skeleton from the side. If the nasal tip is too broad or too bulbous this surgical maneuver will help correct it. It will also help correct the “drooping nasal tip” to some degree, meaning the nasal tip will be raised. Similar surgical alterations of the alar (lower lateral) cartilages can also help in part to correct the “over projecting nasal tip.” In many patients these problems occur in combination and are corrected at the same time. This basic maneuver can be performed with the “open rhinoplasty” technique or the “closed rhinoplasty” technique. If the alar (lower lateral) cartilage is asymmetrical, this is also adjusted at this time. The complex anatomy of the alar (lower lateral) cartilage is so widely varied that many different approaches are needed and used to correct the aesthetic problems of the nasal tip. Additional more complex adjustments of the alar (lower lateral) cartilage are sometimes made with sutures or grafts. It is very important that enough alar cartilage is left in place during the rhinoplasty to adequately support the nasal tip. The red dashed line in the diagram approximates the incision in the alar cartilage (light blue) and the cartilage above the line is removed.

- Alar incision, side view

- Alar incision, front view

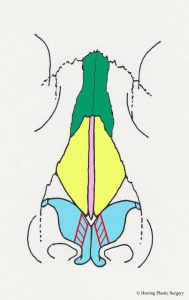

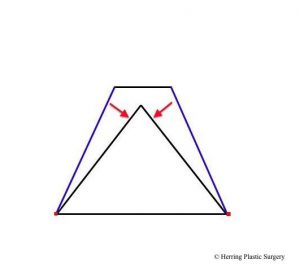

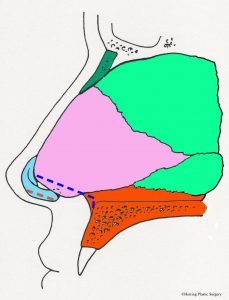

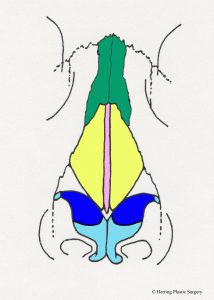

The broad nasal tip is commonly observed in patients seeking rhinoplasty. Another name for the broad nasal tip is the “boxy tip.” This is observed when the alar cartilage is overgrown and too broad. There are a number of surgical maneuvers described to correct this problem, and one is the alar cartilage transection. The alar cartilages are divided on both sides, which facilitates narrowing of the nasal tip. This maneuver is commonly used with other techniques such as the “tip graft” (see section on tip graft below). Another technique that is used alone or in combination with the transection technique is plication (folding) with very small sutures. The sutures are placed in a manner that changes the shape of the alar cartilage. The suturing technique can also increase the projection of the nasal tip in some patients.

- Alar cartilage transection, front view

- Alar cartilage transection, side view

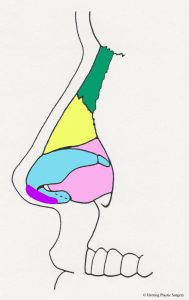

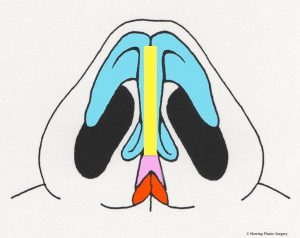

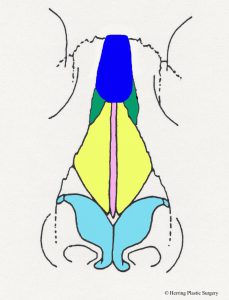

The amorphous (shapeless) nasal tip is treated with a combination of altering the alar (lower lateral) cartilages and a “tip graft.” A tip graft is typically constructed of cartilage that is obtained from another area. Two common areas from which cartilage grafts are obtained are the ear and the nasal septum. Because these grafts are harvested from an inconspicuous (deep inside the nose or inside the ear) area there is no obvious “donor defect” at the area of harvest. The graft is carved into a shape that is customized for the individual needs of the patient. As a result, the grafts will vary in size and shape from patient to patient. The typical nasal tip graft shape is termed a “shield graft.” This cartilage graft is placed and secured in the nasal tip with very small sutures to create more definition on the nasal tip. The cartilage graft mimics the ideal alar (lower lateral) cartilage shape when the desired shape cannot be achieved by altering the natural cartilage alone. The graft covers part of the columella and the medial aspect of the alar (lower lateral) cartilage. The image below is a diagrammatic view of the nasal skeleton from the front. The “shield tip graft” is purple in the lower part of the diagrammatic image below.

- Tip graft, anterior view

- Tip graft, side view

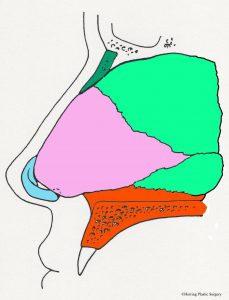

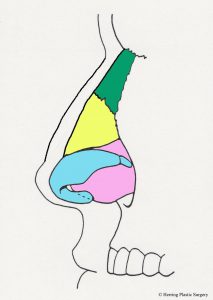

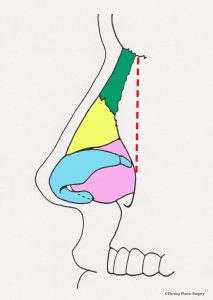

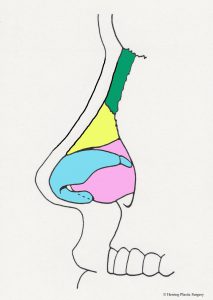

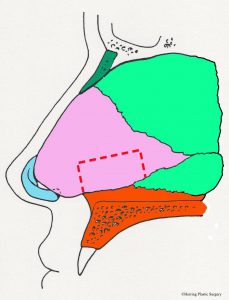

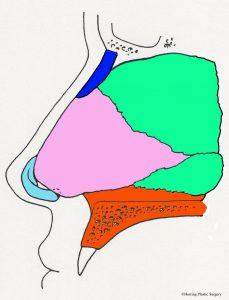

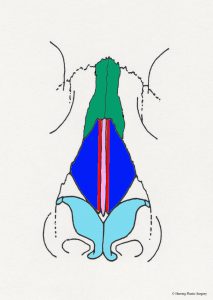

The nasal dorsum is the nasal structure that supports the top of the nose and is what causes the nasal “hump” in some patients. The dorsum of the nose is supported by bone in the upper (approximately) half, and cartilage in the (approximately) lower half. In addition to supporting the dorsum (top) of the nose, it also supports the tip of the nose and the bottom of the nose (the columella). The cartilaginous septum is altered for a prominent dorsum (nasal “hump”), “over projecting nasal tip,” or a hanging columella. In the situation of the “over projection nasal tip” and the hanging columella, the cartilaginous septum may be adjusted in conjunction with the alar (lower lateral) cartilages. The nasal bones are dark green in the images. Additional surgical maneuvers are sometimes needed to narrow the nasal dorsum after it is lowered (see “in-fracture” section below). This involves changing the position of the maxilla (upper jaw bone) and nasal bones to a more medial position. Additional more complex adjustments of the nasal dorsum are sometimes made with grafts (see dorsal graft section below). The diagrammatic views below show the anatomical parts of the nasal septum in the midline as viewed from the side. The nasal bones are represented in dark green. The cartilaginous nasal septum is represented in pink. The bony nasal septum is represented in light green. The alar cartilages are represented in light blue. The maxilla is represented in orange.

- Nasal septum, midline view

In the situation of the prominent nasal dorsum (nasal “hump”) the cartilaginous septum may be adjusted (lowered) in conjunction with the nasal bones. A prominent nasal dorsum is corrected by lowering the cartilaginous septum and nasal bones as noted by the dashed red line. Note also that a small part of the upper lateral cartilage (represented in yellow) is also adjusted at the same time.

- Nasal hump, side view

- Nasal hump reduction, side view

- Nasal hump reduced, side view

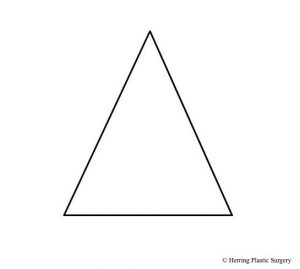

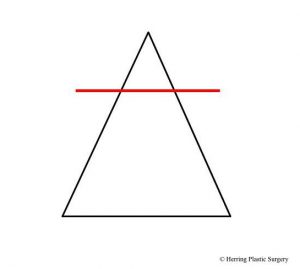

When the dorsum of the nose is lowered to correct a nasal “hump,” the top of the dorsum can appear flat. This will give the dorsum a square shape, as opposed to the normal pyramidal shape. This post dorsum reduction defect is termed the “open boat deformity.” To recreate the normal pyramidal shape the lateral walls of the nose are rotated to the midline. The lateral walls are rotated inward with the pivot point at the base of the nose. The maxilla and nasal bones are separated at the base which allows free rotation and at the same time maintains the blood supply. The in-fracture procedure is necessary when there is a significant lowering of the nasal dorsum. If the dorsum is not lowered significantly this procedure is unnecessary. There are several different techniques to rotate the lateral nasal walls and the choice of the technique depends on the patient’s specific situation. The in-fracture will recreate the natural curve from the glabellar area (between the eyes) to the base of the nose. The cross section diagrams below show a representation of an over-projecting nasal dorsum (nasal “hump”) and the result of a large dorsum reduction. The new unnatural square shape of the nose should be corrected by in-fracture when this occurs. The point of rotation of the lateral nasal walls is represented by the red dots. The horizontal red line shows the level of dorsum reduction to remove the “hump.” The dashed red line shows the part of the over-projecting nasal dorsum that is removed and the new square shape of the nasal dorsum. The blue lines represent the position of the lateral nasal walls before in-fracture and the red arrows show the rotation of the lateral walls to their new position, which is represented by the black line. This maneuver recreates the natural pyramidal shape of the central and upper portion of the nose. The anatomy of the nose is obviously much more complex than represented in the diagrammatic images, but these images give a general idea of the nasal anatomy and the in-fracture maneuver.

- Cross section of mid-nose

- Level of dorsum reduction

- Section of nasal dorsum removed

- In-fracture completed

The diagrammatic image below shows the location of the in-fracture used to correct the flat nasal dorsum (open boat deformity). The rotation point of the lateral walls is represented by the dashed red line and corresponds to the red dots (rotation point) in the diagram above.

- Nasal in-fracture, side view

Dorsal nasal grafts are used when the dorsum of the nose is under-contoured. Grafts used in this area are bone and/or cartilage and usually come from the patient. If a bone graft is chosen it is usually harvested from the hip or the side of the skull. If a cartilage graft is chosen, it can be harvested from the nasal septum, the ear, or the rib cartilage. The graft that is chosen for the dorsum depends somewhat upon the specific situation of the patient. The nasal (septal) cartilage is always the first choice for a pure cartilage graft for the nose for many reasons, including thickness, straight shape, ease of access (same surgical field), and of course biocompatibility. The images below show an undercontoured nasal dorsum and the correction with a dorsal nasal graft represented in purple. Synthetic implants (silicone) for nasal augmentation are not advisable, and historically have had poor long term results.

- Under-contoured nasal dorsum, side view

- Corrected nasal dorsum, side view

Some patients have extra “fullness” at the bottom of the nose that can be corrected during rhinoplasty. The fullness at the bottom of the nose can be a result of alar cartilage excess, or septal cartilage excess, or excess nasal spine (front part of the upper jaw bone), or a combination of all these structures. In some circumstances, the lower part of the alar (lower lateral) cartilage is removed. The alar (lower lateral) cartilage is light blue and the red dashed line in the diagram represents this surgical maneuver. The cartilage below this line is removed. In some circumstances the lower part of the septal cartilage is removed to lessen fullness. In other circumstances, both the alar cartilage and the septal cartilage are removed. The septum is pink in the diagram and the blue dashed line represents this maneuver. The cartilage below the blue dashed line is removed with this maneuver. In some circumstances the anterior nasal spine is altered (lowered) to reduce the fullness of the upper lip. The anterior nasal spine is the front part of the maxillary (upper jaw) bone. The anterior nasal spine is represented by orange in the diagrammatic image below. The area of the anterior maxillary spine below the blue dashed line is removed with this maneuver.

- Full columella correction, side view

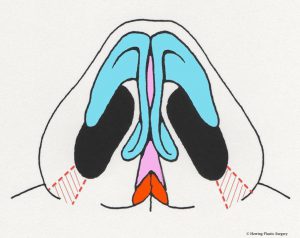

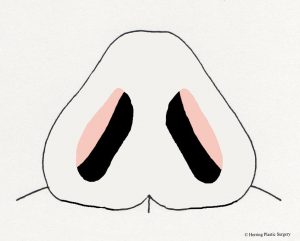

In some patients the base of the nose is too wide. In this context, too wide means that the width of the nasal base is not in proportion with the patient’s facial shape, gender, body habitus, and ethnicity. The nasal width that provided proportion and balance will vary based on those factors in addition to the goals of the patient. The width of the nasal base should not be narrowed to the degree that the airway is compromised. The alar base is narrowed by removing the tissue in the alar base followed by closure of that space with very small sutures. Because of the location of this excision, the scars are very inconspicuous in most patients. The area that is removed is inside red cross hatched areas in the diagram below. This procedure is termed a “Weir excision”.

- Weir excision for wide nasal base, caudal view

The alar strut is used when more support is desired in the nasal tip. This might be needed when the medial aspect of the alar (lower lateral) cartilages is inherently weak, or has been weakened by a surgical maneuver (previous rhinoplasty) to improve shape. The biologic material used to construct the alar strut is autologous cartilage (the patient’s own cartilage). The cartilage used to construct the alar strut is usually harvested from the nasal septum. This cartilage is ideal for this purpose because it is the correct thickness and is also (usually) straight. Because the graft is the patient’s own tissue it is incorporated into the surrounding tissue after it is transplanted.

- Alar strut, caudal view

The upper lateral cartilage is altered during the rhinoplasty to change the midsection of the nose. Because the upper lateral cartilage is a part of the internal nasal valve, alterations must be done while at the same time preserving function. If the upper lateral cartilage is compromised, airway obstruction may occur. The upper lateral cartilage is yellow in the diagram below. If the internal nasal valve is compromised then the airway problem can sometimes be corrected with a “spreader graft.” This graft, which is cartilage, acts a “spacer” between the septum and the upper lateral cartilage. The extra space created by the “spreader graft” opens the airway allowing free air passage.

- Spreader graft, front view

The septal cartilage graft is commonly used when extra tissue is needed to shape the nose. The graft is harvested from the bottom of the septum with an instrument designed specifically for that purpose. The septal cartilage is the correct shape and thickness for most grafting procedures, and the donor area does not cause an aesthetic problem. The septal cartilage graft is simple to harvest and is located in the primary field of surgery, which is also an advantage. Because the perichondrium (the membrane surrounding the cartilage that makes the cartilage) is left intact and in place, there is potential to regenerate the septal cartilage in the area of harvest. It is important to leave an adequate amount of septal cartilage in place after harvest to support the nasal dorsum. If dorsal support is lost it may result in a “saddle nose.” In most circumstances, a very small section or cartilage is needed so an ample amount is left in place for support. Because the cartilage is an autograft (comes from the patient), it is incorporated into the tissue without rejection. The diagramatic image below shows the septal cartilage in pink. The area that is harvested for grafting is outlined in the red dashed line.

- Septal cartilage graft, side view

Ancillary Rhinoplasty Maneuvers

Ancillary rhinoplasty procedures are required much less frequently than the primary rhinoplasty maneuvers described in the previous section. These anatomic problems that these maneuvers correct are seen much less frequently than nasal dorsum or nasal tip problems. These less commonly seen concerns can result from trauma, developmental abnormalities, or a previous rhinoplasty. The correction for these problems can be done at the same time as the primary rhinoplasty procedures reviewed in the previous section.

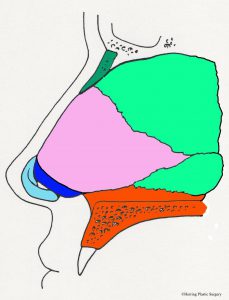

The retracted columella is sometimes seen in a patient seeking a rhinoplasty, but rarely is it the primary concern. The normal anatomy in this area is the columella being slightly lower than the adjacent alar wings. When this situation is reversed, the situation is referred to as a “retracted columella.” As with all areas of the nose, the nasal skeleton supports the nasal skin. In this circumstance, the medial alar cartilage and the septal cartilage do not provide enough projection of the columella to allow the normal anatomical relationship previously described. A cartilage graft needed to correct the problem, and in extreme cases, a bone graft may be needed. In most situations, a cartilage graft will suffice for the correction, and it is easily harvested from the nasal septum which is in the same surgical field. The cartilage graft is carved to the appropriate size and shape, and is then secured with very small sutures. After the graft is placed, the columella will appear lower and more in relation to the alar wings as previously described. The cartilage graft is shown in the diagrammatic image below and is dark blue.

- Columella graft, side view

The inferior (bottom) of the alar wings are either positioned too high or are underdeveloped in some patients. In this circumstance, the height between the columella and the alar wings in more than normal, and the sides of the nose appear too high. The deficiency in this circumstance is cartilage and skin. Because like tissues are preferably used to correct this problem, both skin and cartilage are chosen as the graft. This type of graft is referred to as a composite graft. A composite graft is defined as a graft that is made up of two or more tissue types. The composite graft in this circumstance is very small, and can be easily harvested from the ear. Because the graft is very small, the blood supply can re-establish quickly. The composite graft is placed inside the nose at the caudal (bottom) border of the lateral alar cartilage after the alar rim is “expanded.” The graft is secured with very small sutures. The composite graft acts as a “shim” which will hold the rim of the alar wing down. The alar graft is shown below in the diagrammatic image and is represented in tan.

- Alar graft, caudal view

Wrinkled alar wings (area beside the nasal tip) are not commonly seen in patients presenting for rhinoplasty. The alar wing wrinkling can result from trauma, developmental abnormalities, or a previous rhinoplasty. There are several techniques described for correcting the wrinkled alar wing, and the technique chosen depends upon the severity of the problem. In some circumstances, a simple repair of the natural cartilage is sufficient to correct the problem. In more severe cases, a cartilage graft is used, and it is secured over the natural alar cartilage with very small sutures. This cartilage grafting technique can also be used when there is inadequate alar support which results in external nasal valve collapse. When the external nasal valve collapses this results in airway obstruction during inspiration. Due to the complexity of this procedure, the open rhinoplasty technique is indicated. The lateral alar graft is shown below in the diagrammatic image and is represented in dark blue.

- Alar graft, side view

- Alar graft, front view

The under contoured glabella is another less common reason patients seek rhinoplasty. This is area at the top of the nose between the eyes. The under contoured glabella is not uncommon in patients that have incurred craniomaxillofacial trauma, and specifically naso-ethmoid trauma. When this occurs, the bone fragments can be comminuted (in many small pieces) which makes the primary repair very difficult. When this occurs, and the glabella is under contoured, a graft is sometimes used to recreate the normal contour at the time of the initial repair or at a later time. The graft in this circumstance is usually cranial bone, which is harvested from the side of the skull. Following the “replace like with like” principle, a bone graft would be the primary consideration in this circumstance. The diagrammatic image below shows the glabellar graft, which is represented in dark blue.

- Glabella graft, side view

- Glabella graft, front view

The “pinched nose” perfectly describes the appearance of a patient with loss of support in the middle portion of the nose (the area between the glabella and the nasal tip). A common cause of the pinched nose appearance is a previous rhinoplasty, and specifically an over reduction or displacement of the upper lateral cartilages. In addition to an aesthetic problem, this group of patients may also have a collapse of the internal nasal valve resulting in upper airway obstruction. The pinched nose requires multiple cartilage grafts to repair including a “spreader graft” (see section on spreader grafts in the surgical maneuvers section) and a graft to repair the damaged upper lateral cartilage. The goal in this group of patients is to correct the aesthetic problem and the functional problem. The pinched nose is typically repaired with a septal cartilage graft. Due to the complexity of this pinched nose repair, the open rhinoplasty technique is indicated. The diagrammatic images below show spreader grafts and upper lateral cartilage grafts in red and dark blue respectively.

- The pinched tip front view

- The pinched tip, side view